Aircraft Spruce Canada

Brantford, ON Canada

Corona, CA | Peachtree City, GA

Chicago, IL | Wasilla, AK

Tom Poberezny And The Maturing Of EAA By David Gustafson

| When Tom Poberezny assumed the leadership of EAA as its second president in 1989, he brought a new set of skills, a fresh perspective and a determination to expand the EAA culture. As a result of what Tom brought to the table, EAA entered a new era. It matured. Tom’s professionalism slowly transformed the activities and the magazines to a broader mission, one that expanded on the concept of sport aviation, winning respect from pilots, the government, other organizations and the general public. Tom worked hard to create an environment in which homebuilding would be preserved. He sort of wrapped the movement into the larger cocoon of sport aviation, concurrently assuring that the essential freedoms for innovation, sharing, building and enjoying the tremendous sense of accomplishment that comes with parking a homebuilt on the flightline would be preserved and flourish. He enlarged the showcase for homebuilts, adding every year to the attractions at Oshkosh. What Paul Poberezny had accomplished in creating the homebuilt movement, Tom took to the next level, imbuing the culture with unimpeachable integrity. He did that by maintaining and fusing Paul’s exacting standards for cleanliness, neatness, family values and safety. He was well trained. Tom had grown up in the EAA/homebuilding environment. With the exception of five years at Northwestern University, Tom’s life, from the cradle up to his retirement last year, was surrounded by aviation, homebuilders, fly-ins and an endless stream of visitors in his home who rarely discussed anything that didn’t have some kind of connection to aviation, usually homebuilding. While living in his parents’ home, the basement of his house was the regional social center of homebuilding. That soon expanded into the national and then the international communications hub of the Experimental Amateur Built Aircraft movement. Though Tom cultivated a keen interest in sports, whenever he came home from baseball, basketball or football practice, he found himself returning to all things aviation. His father was gone a lot with military assignments and EAA travel and his mother was working full time with EAA. There were endless meetings at the home and it seemed like there was always a project in progress. It was the world he knew and he just assumed that was what life was all about.

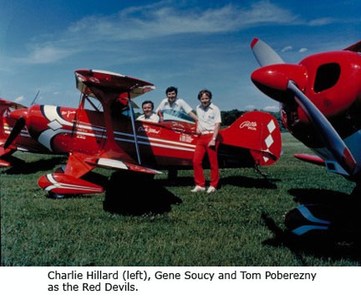

In the mid-70’s, Tom moved up to take over the position of Director of the EAA’s annual Fly-In Convention which had relocated from Timmerman Field in Milwaukee to Rockford Airport in Illinois in 1960 and then in 1970, it settled in Oshkosh. Tom not only planned all of the activities and logistics for what was becoming the world’s largest aviation event, but he planned and participated in the afternoon airshows every day. He had developed an intense interest in aerobatics. Tom, and his dad, Paul, built a Pitts Special to allow Tom to develop his skills. He went to the World Aerobatic Championships in 1972, where he, Charlie Hillard and Gene Soucy won the World Team Trophy. At the conclusion of that event, Tom, Charlie and Gene put on a three-man aerobatic routine and with that, the genesis of The Red Devils Aerobatic Team came into being. The following year Tom went off to the Nationals where he won the title of U.S. National Aerobatic Champion. In 1979, Frank Christensen presented the three pilots with new hybrid copies of Frank’s Christen Eagle biplane and the Christen Eagles were formed. That changed the texture of airshows. They quickly became the most popular civilian aerobatic team in the world, developing an aerial gymnastics routine that was a stand out for precision and fast action, peppered with feats that drew gasps and squeals of exhilaration from the huge audiences that came to see them. It lasted for 25 years. Up through their retirement as a team, the Eagles became synonymous with the EAA Fly-In. Tom considers the time he spent with the Eagles, and especially the time that overlapped with his Presidency at EAA, extremely valuable. “It gave me a whole different perspective and it also provided me credibility with the membership.” He was always running into EAA members while he was out on the airshow circuit. Understandably, Tom considers his work with the Eagles Aerobatic Team, one of the major accomplishments in his life. Charlie, Gene and he brought the thrill of flight to millions of people. That gave Tom a level of confidence and a perception that had a transformative effect on his work as an administrator of EAA. In taking over the Fly-In, Tom gave up his summers. It was practically a year-round job, putting it together and then putting it away. Once that was accomplished and the debriefings were finished, the challenge began anew: scheduling exhibitors, forums, airshows, potties, food vendors, passes, programs, museum activities, site improvements, media arrangements, housing, transportation, air traffic controllers, safety issues, security, divisions activity, VIPs, first visits by military and foreign aircraft, campground logistics, Theatre in the Woods, communications, parking, electrical connections, lawn mowers, tie downs, trash barrels…and a thousand other details that arose during the annual countdown. He had help, of course. Dozens of staff people and thousands of volunteers…all of whom needed leadership, encouragement and the occasional pat on the back. In the month before the start of the Convention, the site went into a 24/7 mode. The days were long, but exhilarating, especially as the display aircraft began to arrive. During the week of the Fly-In, Tom’s day began at 6:00 a.m. and often went past 11:00 at night. His days at the convention were filled with crisis management and finding solutions to hundreds of issues that arose, usually because something had gone wrong or popped up spontaneously. Yet, toward the end of every afternoon, until 1996, he would get out of his Red Three Volkswagen to fly one of the most demanding aerobatic team routines in the world. After 1996, when the Eagles hung it up, the Fly-In grew to such proportions that his decision-making talents were pushed into a realm reserved for people handling the Olympics or Superbowl. Through all of the years that Tom led the Convention, the number, diversity and sophistication of homebuilts continued to grow along with all the other activities.

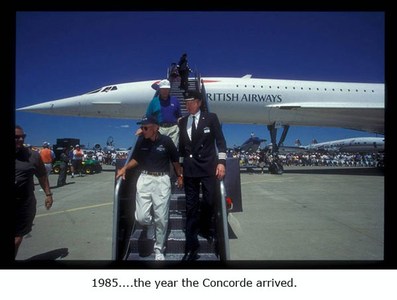

In the process, the EAA Fly-In Convention gained global recognition. Charter flights began coming in from Australia and Europe. In 1985 British Airways sent a copy of the Concorde, four years later the Russians sent an AN-124. More recently, Airbus brought their new 380, Jet Blue came in with an Embraer 190 and then an Airbus 320, and the world’s finest airshow pilots came back again and again, volunteering their services for crowds that grew with every passing year. The Warbirds seemed to increase in numbers each year, staging the largest flying assemblage of military aircraft anywhere in the world. The flightline changed dramatically, when the editor of Sport Aviation, Jack Cox, suggested honoring “classic” aircraft (airplanes over 50 years old) by parking them among the display aircraft. They now take up nearly half of the space in the display aircraft area. The ultralights and rotorcraft operate their own airport within the boundaries of the main airport. Pioneer Airpark is kept busy with KidVenture, helicopters, and the growing number of dirigibles that turn up at what has become known as AirVenture. Every year Tom added to the activities. The number of exhibitors grew tremendously, with more and more kit manufacturers turning people’s dreams into realities.

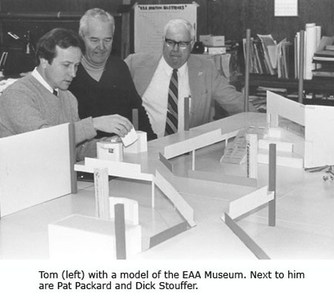

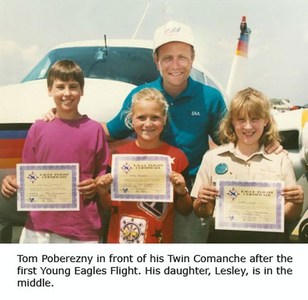

Through it all, the EAA continued to add to its membership roll. In Tom’s tenure the number of EAA members doubled. Sport Aviation magazine slowly expanded its purview from its near total focus on homebuilts to a broader reach that encompassed all forms of recreational flight. The idea of using an aircraft for fun, for adventure and for enriching a weekend experience gained in recognition and respect. Warbirds, antiques, classics and ultralights all took on greater meaning as more and more people came into the EAA fold. Tom spearheaded the movement to create the Sport Pilot license along with an entirely new category of Light Sport Aircraft. That brought over a hundred new designs into the world of sport aviation, broadening the meaning of the term. Recreational flying spawned an industry that came together annually at the world’s largest and busiest aviation event. Though Tom never had his father’s passion for homebuilding, he never lost sight of the importance and value of homebuilding. He just approached it in a different way. He is a Poberezny and he is his father’s son, but he is also a very different individual. Paul is emotional. Tom is controlled. Paul is gregarious. Tom seems almost shy at times. Paul has a passion for homebuilts. Tom has a passion for aviation. Paul is spontaneous. Tom is organized. Their strengths cover the other’s weaknesses. They complement each other. They’re like yin and yang. The one thing they have in common has been their desire to keep homebuilding free of over-regulation, and make EAA an example of the very highest standards in everything they pursue. Tom has certainly left his mark. Looking back, he is proud of the growth of AirVenture both from the standpoint of numbers and values. “It’s grown from a fairly small event with a lot of heart in it, to the world’s premiere aviation event,” he said. “It’s totally unique and there’s not another event like Oshkosh in the world.” He also harbors a sense of fulfillment and satisfaction over the development and status of the EAA Aviation Center in Oshkosh. Tom was the essential player in designing and then attracting the funds that were needed to make the structure that houses the EAA administration and the museum facilities. “It’s become the year-round home for aviation, not just for EAA but for all aviation enthusiasts. It’s created a permanency that doesn’t exist anywhere else. The headquarters, the air academy facilities, the Lodge, the Weeks Hangar, the museum; these all give aviation a sense of permanency. It’s got great depth.” And class. It is the combination of all these elements that has given homebuilding a longevity, credibility and portal it might never have experienced otherwise. For Tom, it was the realization of a dream…one that every EAA member can share in. Understandably, Tom is also very proud of the Young Eagles Program, which he initiated. In 1992 the program was launched with the goal of taking a million kids for an airplane ride prior to the 100th anniversary of powered flight in 2003. They Tom has always admired homebuilding, always advocated for it. It’s a science and art form that has constantly evolved since he assumed a leadership role at EAA. Tom saw the introduction of homebuilding kits at Oshkosh. It’s a little known fact that Glenn Curtiss was the first aircraft manufacturer to sell an airplane kit in 1911. Back then the builder got a set of plans, some oak and hemlock boards, baling wire and some bolts of muslin. It’s doubtful many of them ever flew. Others followed, but no one had ever come close to what Frank Christensen did in 1978, when he brought the first Eagle kit to Oshkosh. That changed kitbuilding forever. Frank set a standard for excellence that some have aspired to, but none have exceeded. It launched a new industry. “Scratchbuilding” had been the mainstay of homebuilders up to that point. Kitbuilding quickly increased the audience and participants in the movement. Of the 30,000 homebuilts now on the FAA registry, it’s likely that half of them are from kits. There could be as many as 30,000 others under construction. “Consider the amount of product that has been bought and utilized by homebuilders,” said Tom. “EAAers have bought tens of thousands of engines, tires, and tons of steel and aluminum over the years. They’ve purchased trainloads of foam and fiberglass.” Burt Rutan had introduced the use of composite materials in his VariEze in 1975, bringing forth a technology that would ultimately wind up in Boeing’s new Dreamliner. A couple of brothers named Klapmeier also picked up on Rutan’s composites, designed an aircraft called the Cirrus VK-30 and eventually delivered the SR-20/22. “The homebuilt movement is the core of what Oshkosh is all about. It’s a center for innovation and entrepreneurship, for learning and sharing. That, in turn, impacts the whole aviation community. Oshkosh keeps the dream alive for thousands of people who are still contemplating whether they should build or buy. For so many people it’s the only way they could afford to fly, to own their own airplane. Or it’s the one way they could enjoy the special kind of performance and style they want in an aircraft.”

The designs, the kits and the technology keep improving. “Look at the RV series of planes. The quality of the kits and flight performance are outstanding, and the flying characteristics are equal to many of the certificated aircraft that are out there already. And then, when you look at what people are installing in their instrument panels…they’re airline quality in some cases, and more sophisticated than many certificated aircraft. The homebuilt movement has been the bastion for innovation for years. Electric flight is an outgrowth of homebuilding. Technology and kit refinements have transformed the world of homebuilding. Every year I have talked to engineers from Piper, Beechcraft and Cessna, even some from Boeing. They come to Oshkosh to see the newest innovations. They talk to the designers to discover how they developed their ideas and then go home to figure out how they can apply the same technology in the certificated world. The impact has been tremendous.” Tom feels his greatest contribution to the world of homebuilding has been to protect the regulatory opportunity for homebuilders. The rules really haven’t changed in six decades. On the other hand, when you compare the size of the FARs in 1953, with the amount of regulations that exist today, the contrast goes beyond dramatic. Essentially, the 51% rule still governs homebuilding. In addition to protecting the opportunity to build, Tom worked at improving Oshkosh as a place to share knowledge and to tap into the homebuilder’s network. He realizes that thousands of people come to inspect homebuilts, wishing they could build one, but they are held back because of their lack of skills and knowledge. So often, they would come to Oshkosh and find others like themselves. There are now so many people who have gone through the experience of building that the dreamers who visit Oshkosh find themselves surrounded by guidance and knowledge that makes it possible for them to convert their dream to a reality. “Don’t think you can’t do it. Our goal, at EAA, has been to provide the knowledge and the network to keep homebuilding alive.” Tom has a very high level of respect and admiration for the unsung heroes in the movement. They’re people you’ve never heard about, but who built one or multiple airplanes, and have shared their knowledge and skills to help others…sometimes dozens of others in setting up a workshop and launching a project. Tom firmly believes that every person who has designed an airplane, built one or helped someone else build one is a “star” in the homebuilt movement. Tom took an idea, a passion that was defined by his dad and he grew it |

Aircraft Spruce Canada

Aircraft Spruce Canada

made it. They kept the program going and have now taken nearly 1.7 million kids on Young Eagles flights. It has become an integral part of EAA’s mission and it was EAA members who made that possible. “It’s become the world’s most successful youth education program for aviation,” said Tom. And it’s involved tens of thousands of EAA members who volunteered their time, aircraft and avgas.

made it. They kept the program going and have now taken nearly 1.7 million kids on Young Eagles flights. It has become an integral part of EAA’s mission and it was EAA members who made that possible. “It’s become the world’s most successful youth education program for aviation,” said Tom. And it’s involved tens of thousands of EAA members who volunteered their time, aircraft and avgas.

“Protecting the 51% rule was my number one priority. That rule and the regulations that accompany it is the essence of the movement. Without that, there is no homebuilt movement. To protect that took a combination of efforts. We engaged in an on-going program of education demonstrating to the FAA that the way to enhanced safety was through education, not regulation. Designees, tech counselors, flight advisors, EAA Chapters…the list goes on and on…they all played a part in educating people. They have matured tremendously in the past half century. We brought the FAA to Oshkosh, not just during the Fly-In, but in the off-season to demonstrate our commitment to safety. The FAA realized that the homebuilt movement was a necessary asset for innovation, but FAA also required an acceptable level of safety. We kept confrontation out of our discussions with them, avoiding a sense of crisis, while working quietly out of the spotlight. Keeping the original 51% regulation in tact was probably my greatest accomplishment. The homebuilt movement needs to be protected and respected. Through its actions, EAA has demonstrated integrity which earned the respect of the federal authorities. The day that there’s a regulatory change that restricts the opportunity to build, will be a sad day for aviation and I hope that day never comes.”

“Protecting the 51% rule was my number one priority. That rule and the regulations that accompany it is the essence of the movement. Without that, there is no homebuilt movement. To protect that took a combination of efforts. We engaged in an on-going program of education demonstrating to the FAA that the way to enhanced safety was through education, not regulation. Designees, tech counselors, flight advisors, EAA Chapters…the list goes on and on…they all played a part in educating people. They have matured tremendously in the past half century. We brought the FAA to Oshkosh, not just during the Fly-In, but in the off-season to demonstrate our commitment to safety. The FAA realized that the homebuilt movement was a necessary asset for innovation, but FAA also required an acceptable level of safety. We kept confrontation out of our discussions with them, avoiding a sense of crisis, while working quietly out of the spotlight. Keeping the original 51% regulation in tact was probably my greatest accomplishment. The homebuilt movement needs to be protected and respected. Through its actions, EAA has demonstrated integrity which earned the respect of the federal authorities. The day that there’s a regulatory change that restricts the opportunity to build, will be a sad day for aviation and I hope that day never comes.”

tremendously. “My dad is a rare person. But I had the skills and the commitment to take his idea and grow it.” Tom took EAA to a higher, considerably more mature level. In doing so, he brought together a much larger group of people who have a common interest and a passion for flying. Tom made a tremendous difference to EAA and to aviation and he left it far better than it was when he arrived. Try to imagine aviation without those splendid EAA Headquarters facilities, without AirVenture, without Young Eagles, without the Air Academies, without a world class aviation museum that honors designers, builders, aerobatics, antiques, warbirds, ultralights and rotorcraft…. Without the Poberezny legacy, general and sport aviation just wouldn’t be the same.

tremendously. “My dad is a rare person. But I had the skills and the commitment to take his idea and grow it.” Tom took EAA to a higher, considerably more mature level. In doing so, he brought together a much larger group of people who have a common interest and a passion for flying. Tom made a tremendous difference to EAA and to aviation and he left it far better than it was when he arrived. Try to imagine aviation without those splendid EAA Headquarters facilities, without AirVenture, without Young Eagles, without the Air Academies, without a world class aviation museum that honors designers, builders, aerobatics, antiques, warbirds, ultralights and rotorcraft…. Without the Poberezny legacy, general and sport aviation just wouldn’t be the same.